The French Trade Axe (hache de traite)

The term French trade axe or "hache de traite" applied to many types of axes traded during the French regime in New-France. In this section, we will be discussing the colonially made trade axe manufactured by blacksmiths in the St. Lawrence Valley, at the Fur Trade Post in the interior as well as certain axes manufactured in France that were specially referred to as "hache de traite" on invoices destined for the North American colony. It becomes very tricky in attempting to distinguish a "hache de traite" from the "hache biscayenne". Certain characteristics, when comparing various axes found in a French context help us in isolating this specific type of axe. One certain characteristic is the crudeness of it's construction as well as the cost saving tactics in manufacturing an axe while attempting to minimize the use of metal.

Having another look at the Rainy Lake Post invoice from 1741 proves that there were distinguishable features between the Biscayan and Trade axe.

Many questions arise when looking at this invoice:

Were these so called "Trade axes" made specifically for the trade by colonial blacksmiths?

Were these so called "Trade axes" made specifically for the trade by both colonial blacksmiths and European manufacturers depending on supply/demand?

Were there two different manufacturing centers for trade axes in Europe producing two distinctively different axes? (One from the Biscay provinces and the other possibly elsewhere in France or Europe)

Was the distinguishable feature between the Biscayan and "Trade axe" the durable strip of steel on the cutting edge that may of been added or omitted in the manufacturing process?

Was the trade axe a cruder and cheaper copy of the Biscayan axe?

Were these "Trade axes" also referred to as "hache du pays" as seen on other period invoices?

Were the terms used for axe types subject to the outfitter, merchant or supplier's terminology (trends and fashions etc) at that particular moment in time?

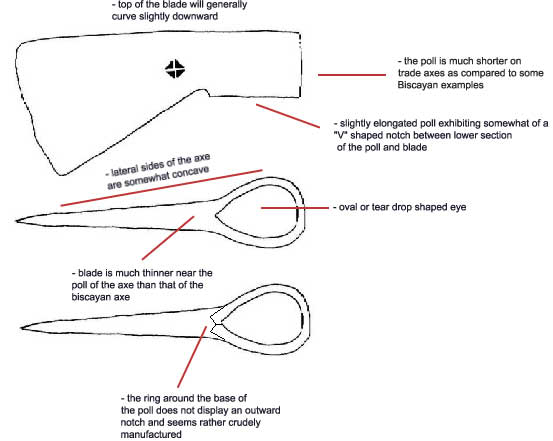

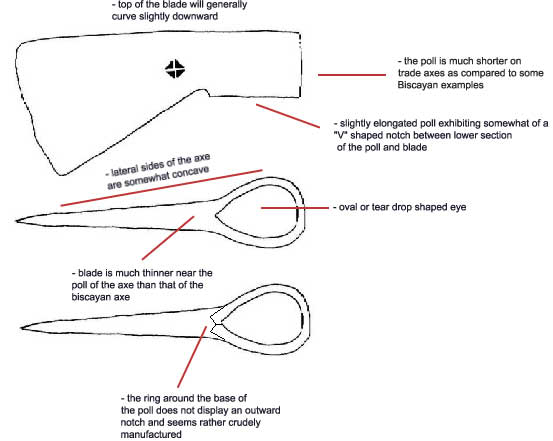

We notice when taking at look at many French context axes that the side profile and the marking system for both type are quite similar. The differences are only noticeable from a top or bottom view of the axe head: the contour of the sides, the thickness of the blade near the poll, the height of the poll, as well as the workmanship involved in the axe's construction.

The following account shows that some "Trade axes" cost considerably less than that of axes with steel edges. As such, certain "Trade axes" contained no steel edges or bits.

In 1702, the Quebec outfitter Martel notes that in a consignment of goods provided to a Labrador trader in 1702 included: "2 large axes with a steel edge, two small axes with a steel edge, and 24 trade axes, priced at 5,3 and 1.2 livres apiece"1 (A.N.Q.-Q.,Inventaire d'une Collection...Dossier 397, original ms., 19 mai, 1702.)

The next account however notes that some locally made axes (Trade axe type?) were manufactured with steel edges or steel bits.

In 1732, Monière noted "12 locally made-made axe (hache du pays) with a steel edge" destined for the Nipigon Post at 2.25 livres apiece. (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4,p. 168; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-848)

When looking at these records, it is clear that we can rule out the possibility that the main distinguishable feature between Biscayan axes and Trade axes was the addition or omission of steel edges.

Let's now explore the possibility that these so called "Trade axes" were manufactured in the colonies as opposed to them being solemnly manufactured in Europe:

In 1721, a blacksmith called Brunet manufactured 24 axes. (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4,p. 219; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-847)

Also in 1721, a smith named Lavallée made small axes and tomahawks for the merchant Monière (a local Montreal merchant operating in the first half of the 18th century) . (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4,p. 216; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-847)

In 1722, Brunet made another 20 axes for Monière. (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4,p. 429; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-847)

In 1732, Monière "shipped "locally-made" axes (hache du pays) to the Nipigon post." 1 (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4,p. 168; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-848)

In 1733, the blacksmith named "Fleur d'Epée" made 12 axes with a steel edge for Monière. (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-848)

In 1736, the blacksmith Boutin made large axes for two of Monière's clients; "one of them was for Monsieur Giasson at the Sioux post, while two others were for Monsieur Phillipeau, who was departing for the Illinois country."1 (MMR, Monière, Vol. 4. p. 789; N.A.C., MG 23/GIII 25: Microfilm M-848)

In 1750, a particular local Montreal blacksmith was asked by Monière to manufacture "two lots of axes; one group containing forty units weight 84 1/2 pounds, averaging 2.11 pounds apiece, while the other set of forty weighed 80 pounds, averaging an even 2 pounds apiece." 1 (Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec, MMR, Monière, Blotter 1739-1751, p.975)

In 1760, Monière once again paid a blacksmith to produce 36 axes, each axe weighing 2 1/2 pound each. (Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec, MMR, Monière, Brouillard mss., p. 118)

One of the most important entries from the MMRPs is an order placed by Monière in 1735 to a blacksmith named Delorme that manufactured 135 trade axes and 12 duty-axes (hache de service) destined for the Illinois country. (MMR, Monièere, Journal No. A, 1752-1753; N.A.C., Microfilm M-850, Vol. 13, p.42). When looking at the various large service axes we have found on archeological sites especially the ones from Crown Point found in a French context, (Please see the "The French Duty-axe (hache de service)" page for pictures) we can clearly see the ressemblance in the contruction methods between the "Trade axe" type and the "Duty-axe" axe (oval/tear drop shaped eye, thin blade, concave lateral sides etc)

The smith Delorme most likely manufactured both his Trade axes and Duty-axes in a similar fashion or style, confirming to a certain extent that the so called "Trade axe" type or form is simply a cheap colonial copy of the Biscayan axe that was so popular among natives in New-France. In fact, we could say that this new type of axe served as a base model for the next generation of trade axes manufactured by British Trade companies after the fall of New-France.

Finally, we could argue that this axe type is a direct result of these various factors :

the short supply of iron ore would lead to the use of less iron per axe, explaining the occurance of thinner blade and shorter polls on trade axes

the lack of highly skilled blacksmiths, plentiful labour and proper equipment/tools would lead to the production of cruder and cheaper made axes over time unlike the manufacturing centers in Europe such as the town of Bayonne which had a corporation of arts and trades dealing with the manufacture of high quality weapons and tools such as the Biscayan axe

To quote William R. Fitzgerarld : "Quality decreased quite rapidly, serving a number of European ends. Less iron was required for each axe, more lighter axes could be transported, and inferior axes would lead to more frequent replacement. "

| Characteristics of the French Trade Axe (hache de traite) |

|

(Trade axe type, top, bottom and side view. Collection J.-Henri Fortin, Québec, Canada.)

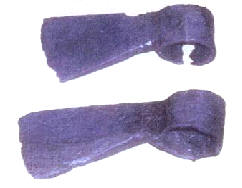

There are many many mentions of the French trade axe (hache de traite) which makes it hard to try and cross reference this so called type with dug specimens. The wreck of the La Salle's ship "La Belle" in 1687 contained a shipment of axes, most likely for the trade. These types of axes seem to be poorly constructed with a thin blade and a tear drop or shaped or round eye unlike the early types of trade axes found in Huronia that possess flat oval eyes and very thick blades especially near the poll.

|

|

|

Axes found on the La Belle shipwreck, 1687. (* Please notice the thin blades and round eyes) (Picture by Ken Hamilton - Permission given by Ken Hamilton to reproduce.) |

|

|

| (Top left) Here you have 2

types of trade axes from the Dann site (Albany State Museum). The

axe on the left would be considered a Biscayan type axe and on the right

you will notice a trade axe. It is quite apparent that both these

axe are manufactured quite differently. The trade axe possesses a

very thin blade and tear drop shaped eye as compared to the Biscayan one

that displays a very thick blade near the poll and a flattened oval shaped

eye. (Top right) Detail of the maker's mark from the trade axe on

the right. (Bottom) What is interesting is that they both use the same marking system with marker's marks. The top axe has a one "cross-in-a-circle" maker's mark whereas the bottom one displays 3 "cross-in-a-circle" marks. *Picture by Ken Hamilton - Permission given by Ken Hamilton to reproduce. |

|

| Here is an example of what I would think is a colonial made trade axe with a double "cross-in-a-circle" mark. Notice how the marks overlap one another. (Found in Michigan in a French context) |

|

|

|

| Here is an example of what I would think is a colonial made trade axe with a double "cross-in-a-circle" mark. Notice how the marks overlap one another in a similar way to the trade axe displayed above. As for history, this artifact was dug in the 60's at Point aux Pins, near the entrance to Lake Superior on the St. Mary's river about 4 miles above the rapids at the historic twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie Michigan and Ontario. Louis Denis Sieur de la Ronde established a ship yard at Point aux Pins and built the first decked vessel to sail on Lake Superior from here in 1735. Artifacts from prehistoric times and from all periods of the fur trade have been found here. This axe is without a doubt of French context. | |

|

|

|

|

1. Timothy J. Kent, "Ft Pontchartrain at Detroit, Volumes I & II", Silver Fox Enterprises, 2001.